notebook

Programming Schumann’s Études symphoniques

29 Sep 2017

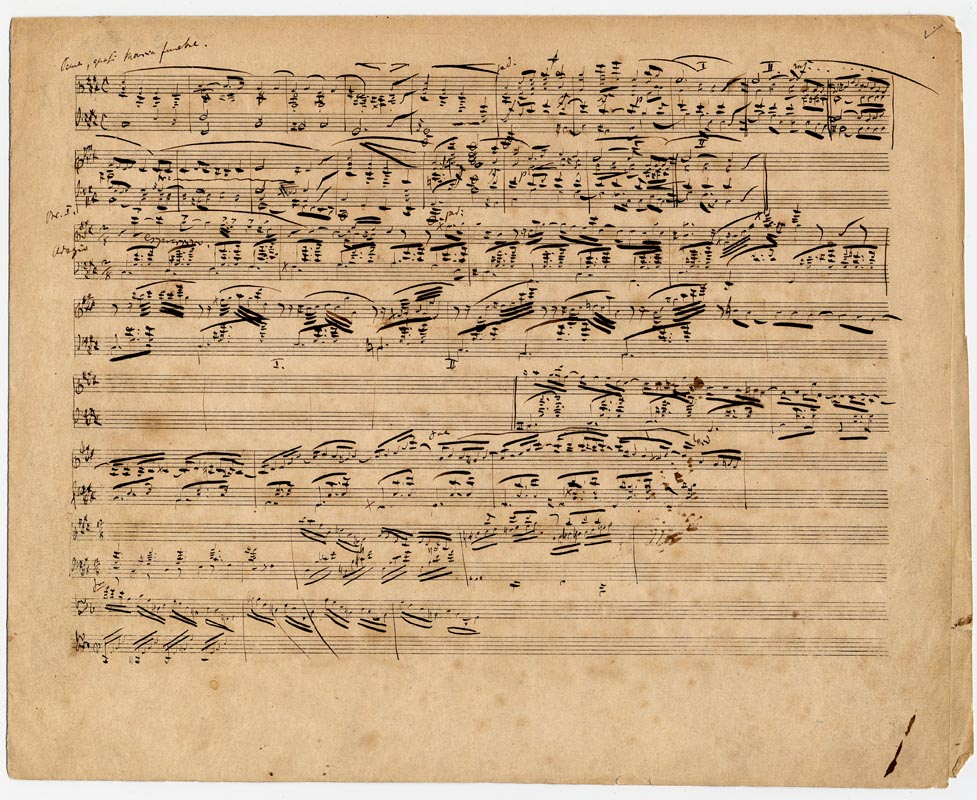

Manuscript sketch of Schumann’s op. 13, cached from the Yale music library

Most of the studies in Schumann’s Études symphoniques, op. 13, are variations on a theme. Taking a page from Beethoven’s Diabelli Variations op. 120, the theme serves more as inspiration than template from which Schumann composed his variations.

In the first version published in 1837, Schumann notes that the theme was based on “la Composition d’un Amateur”. The amateur here was Baron von Fricken, the guardian of Ernestine von Fricken, who is the Estrella in his Carnaval op. 9 and Schumann’s ex-fiancée.

The first version contains the theme and 12 etudes. The third, ninth, and twelfth etudes are not marked as variations. The finale is a variation of another theme from Heinrich Marschner’s opera Der Templer und die Jüdin (The Templar and the Jewish Woman):

Du stolzes England freue dich (Proud England, rejoice!) from Der Templer und die Jüdin

Etude 12 (finale) of Schumann’s Études symphoniques, op. 13

He wrote six additional variations that he ultimately scrapped because he found it difficult to order them. Five of them were salvaged by Brahms and published as a supplement in 1873, almost two decades after Schumann’s death. The variations are beautiful and deserve being played. So many pianists have tried to finish the task Schumann gave up on.

The Variations

Theme

Etude 1 (Variation 1)

Etude 2 (Variation 2)

Etude 3

Etude 4 (Variation 3)

Etude 5 (Variation 4)

Etude 6 (Variation 5)

Etude 7 (Variation 6)

Etude 8 (Variation 7)

Etude 9

Etude 10 (Variation 8)

Etude 11 (Variation 9)

Etude 12

Supplementary Etude 1

Supplementary Etude 2

Supplementary Etude 3

Supplementary Etude 4

Supplementary Etude 5

Thinking about how to put together the ordering, characteristics of each movement should be considered1:

| Key | Time | Character | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theme | c |

funeral march | |

| Etude 1 | c |

military march | |

| Etude 2 | c |

romance | |

| Etude 3 | c |

scherzo | |

| Etude 4 | c |

soldier’s march | |

| Etude 5 | c |

scherzo | |

| Etude 6 | c |

agitato | |

| Etude 7 | E | heroic | |

| Etude 8 | c |

French overture | |

| Etude 9 | c |

scherzo | |

| Etude 10 | c |

energetic | |

| Etude 11 | g |

lyrical | |

| Etude 12 | D |

fanfare | |

| Supp. Etude 1 | c |

arabesque | |

| Supp. Etude 2 | c |

waltz, pastoral | |

| Supp. Etude 3 | c |

despondent | |

| Supp. Etude 4 | c |

mazurka | |

| Supp. Etude 5 | D |

dream |

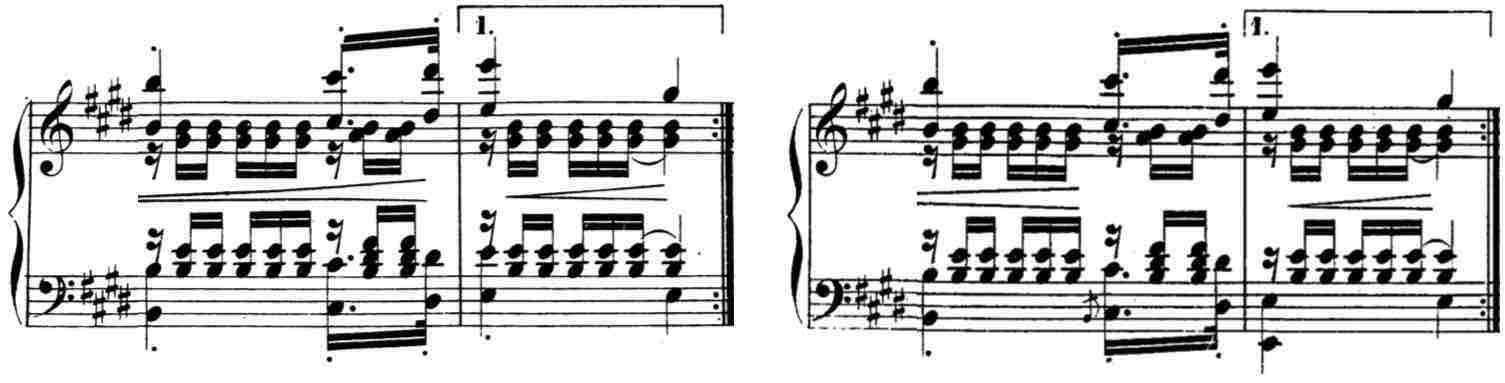

Complicating matters are the differences even between the “standard” variations. A second edition published in 1852 contained edits, excised the third and ninth etudes since they were hardly variations, and was renamed Études en forme de variations. A third edition published in 1861, five years after Schumann’s death, reinstated the non-variation etudes and attempted to reconcile the differences.

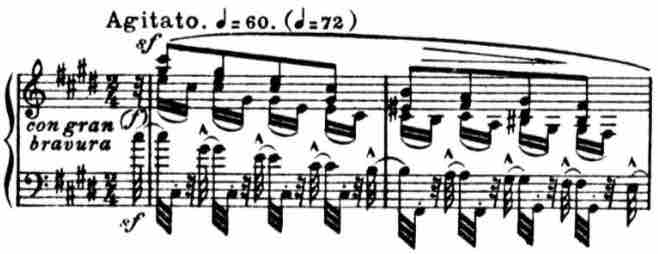

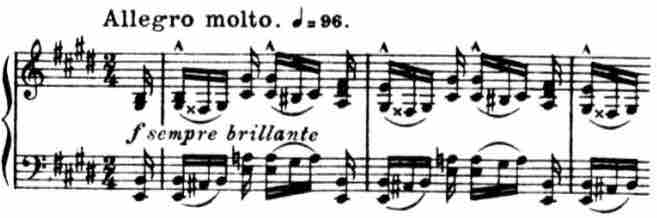

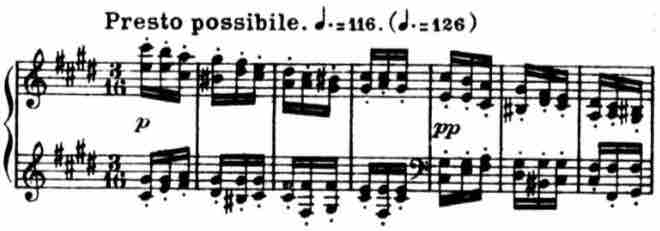

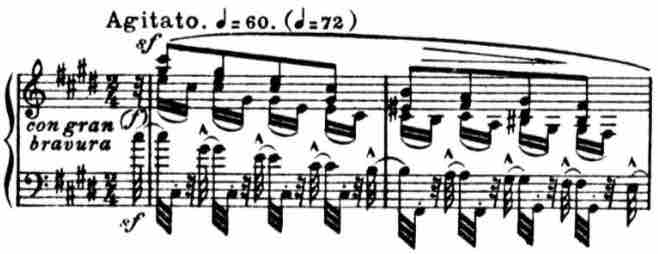

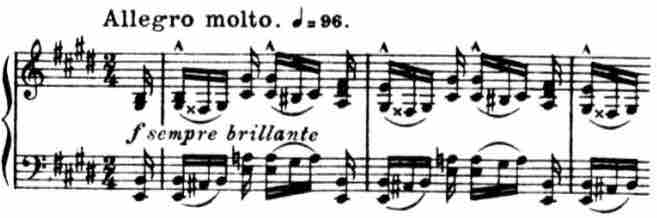

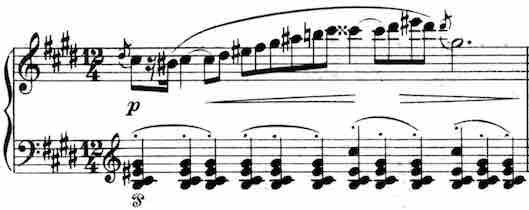

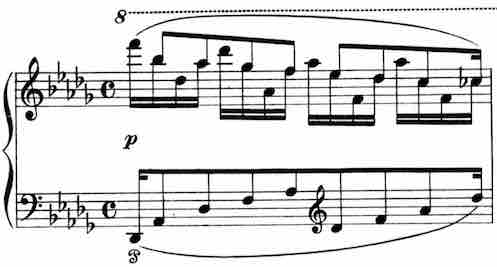

These differences appear small but are substantive. Following are some examples, with the first edition on the left:

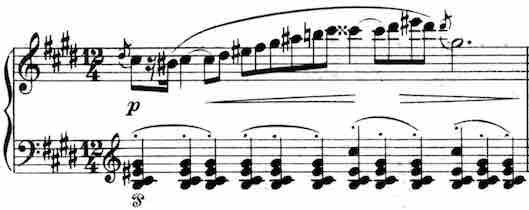

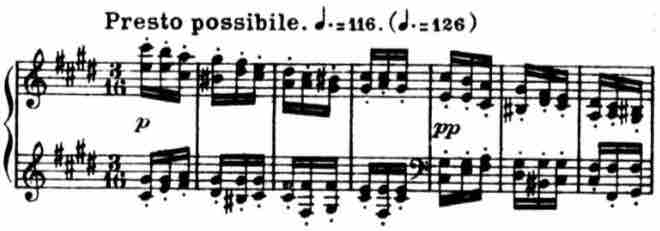

In the first version, Etude 1 includes a tympani line when the theme returns:

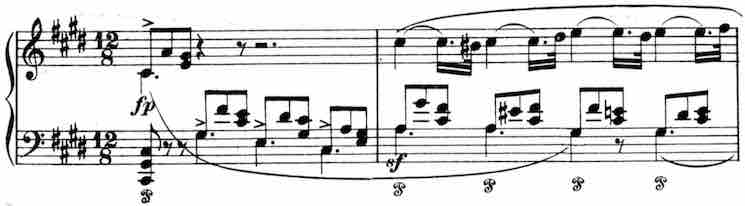

Etude 2 contains a more dramatic left-hand part in a later version:

Etude 4 shifts the

Etude 9 repeats the second section in a later version:

Etude 10 has a rhythmically consistent right-hand line in a later version:

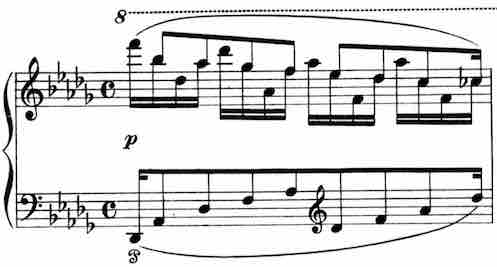

In Etude 11, the first version includes an introductory measure from the left hand, while the second edition repeats the first section. The third edition contains both.

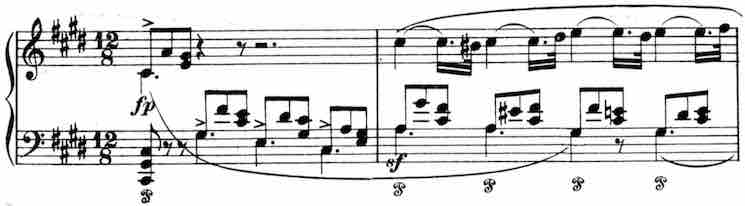

Etude 12 contains a different middle section when the theme returns in the first version, while the second version repeats the theme wholesale.

Survey of etude orderings1

There are two schemes that are generally used to insert the posthumous variations.

The first is to insert them individually within the original order. Cortot appears to be the first to do this, and he made an influential recording of them in 1929.

The second scheme inserts the 5 variations in order as a group between Etudes 5 and 6. Pianists including Richter and Pollini use this. Aimard inserted them between Etudes 7 and 8. Ashkenazy inserted them between Etudes 9 and 10.

Cortot, 1929

Here’s how Cortot inserted the variations:

| Theme | c funeral march |

|

| Etude 1 | c military march |

|

| Supp. Etude 1 | c arabesque |

|

| Etude 2 | c romance |

|

| Etude 3 | c scherzo |

|

| Etude 4 | c soldier’s march |

|

| Etude 5 | c scherzo |

|

| Supp. Etude 4 | c mazurka |

|

| Etude 6 | c agitato |

|

| Etude 7 | E heroic |

|

| Supp. Etude 2 | c waltz, pastoral |

|

| Supp. Etude 5 | D dream |

|

| Etude 8 | c French overture |

|

| Etude 9 | c scherzo |

|

| Supp. Etude 3 | c despondent |

|

| Etude 10 | c energetic |

|

| Etude 11 | g lyrical |

|

| Etude 12 | D fanfare |

|

Other orderings

As a comparison against Cortot, here are other orderings2:

| Cortot 1929 | Brendel 1990 | Arrau 1976 | Kissin 1990 | Cziffra 1965 | Anda 1964? | Wild 2000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Theme 1 S 1 2 3 4 5 S 4 6 7 S 2 S 5 8 9 S 3 10 11 12 |

Theme S 3 1 S 1 S 2 2 3 4 5 S 4 6 7 8 9 S 5 10 11 12 |

Theme 1 S 1 2 3 4 5 6 S 2 7 S 3 S 4 8 S 5 9 10 11 12 |

Theme 1 S 1 2 3 4 5 6 S 4 S 5 7 S 3 8 9 S 2 10 11 12 |

Theme 1 S 1 2 3 S 2 4 5 6 7 8 9 S 4 10 11 12 |

Theme 1 2 3 4 5 6 S 2 7 8 S 5 9 10 11 12 |

Theme 1 2 3 4 5 S 1 6 S 2 S 3 7 8 S 4 9 S 5 10 11 12 |

-

Yang, Teng-Kai (2014). The Ordering of Schumann’s Symphonic Etudes, op. 13: Incorporating the Posthumous Variations. ↩ ↩2

-

Seregow, Michael (2014). The Life and Times of Schumann’s Symphonic Etudes, opus 13. ↩